Effect of Dietary Supplementation with Silicon on Free Amino Acid Levels in Egg Yolk and Blood Vessel Strength in Laying Hens

- KIWITA

- Jan 15

- 12 min read

Effect of Dietary Supplementation with Silicon on Free Amino Acid Levels in

Egg Yolk and Blood Vessel Strength in Laying Hens

Junpei Yamamoto1, Chika Kitaoka1, Ai Mekaru2, Mitsuhiro Yanagi2.

Kazutoshi Sugita3, Yasunari Yokota4,

Yoko Kawamura4, Fumio Nogata4, Mitsuo Terasawa5, Fumitoshi Asai3

and Yuko Kato-Yoshinaga1*

School of Life and Environmental Science, Azabu University, 1-17-71, Fuchinobe.

Chuo-ku, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-5201

2. Research Institute for Animal Science in Biochemistry and Toxicology,

3-7-11, Hashimotodai, Midori-ku, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-0132

3School of Veterinary Medicine, Azabu University, 1-17-71, Fuchinobe, Chuo-ku, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-5201

4Faculty of Engineering, Gifu University, 1-1, Yanagito, Gifu, Gifu 501-1193

5Living Body Health Science Institute, 2-15-75, Tadao, Machida, Tokyo 194-0021

The present study aimed to examine the effects of 10-week dietary supplementation with silicon on free amino acid levels in egg yolk and on blood vessel strength in laying hens. We analyzed the levels of free amino acids in the yolk and white of eggs and blood vessel strength by high-performance liquid chromatography and tensile test, respectively. In initial experiments, 1 % and 5% commercial product containing silicon had no effects on body weight. body weight gain, egg-laying rate, water intake, and food consumption relative to control. These data suggest that silicon intake at the evaluated concentrations was minimally toxic in the laying hens. The levels of aspartic acid. threonine, and alanine were significantly higher in the yolk of eggs laid by the hens receiving 5% dietary silicon product supplementation than in those laid by hens receiving 1% silicon product. In addition, blood vessel strength of the descending aorta was significantly higher in the 5% silicon product treated group than the control group. These results indicate that dietary supplementation with silicon might have beneficial effects on egg yolk taste and blood vessel strength in laying hens.

(Received Jun. 7. 2017: Accepted Aug. 14, 2017)

Keywords: silicon, laying hen, free amino acid, blood vessel strength

Silicon (Si: atomic number 14) is one of the most abundant elements in the living world, and is considered an essential trace element for humans1). In living organisms, silicon is widely distributed in connective tissues such as skin and bones. However, since it has been reported that there is a positive correlation between silicon intake and bone density (2), it is used as a supplement to prevent osteoporosis after menopause. It was reported that silicon is an essential element for chickens3).Subsequently, it was reported that silicon is involved in bone formation, increase in bone strength, and connective tissue formation4)-6), and silicon is important in the formation of body tissues in chickens. On the other hand, Kawamura et al. reported that the mechanical strength of blood vessels increased in rats that ingested silicon.7) Thus, there are several reports regarding the physiological functions of silicon. However, there are very few studies on its effect on the taste of foods.In our previous research, we found that when silicon is administered to broiler chickens, the amount of free amino acids that give umami and sweetness increases in the edible parts, and the taste quality decreases. In this study, we administered drinking water supplemented with silicon to laying hens for 10 weeks, examined changes in free amino acids in egg yolk, and examined the effect on the mechanical strength of blood vessels in laying hens. .

1 1-17-71 Fuchinobe, Chuo-ku, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-5201, 2 3-7-11 Hashimotodai, Midori-ku, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-0132,

3 1-17-71 Fuchinobe, Chuo-ku, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-5201, 4 1-1 Yanagido, Gifu, Gifu 501-1193,

5 2-15-75 Tadao, Machida City, Tokyo 194-0021

*Corresponding author, yoshinaga@azabu-u.ac.jp

Journal of the Japanese Society of Food Science and Technology Volume 65, Issue 1 January 2018

Experimental Method

1.Animals

The animal experiments in this study were conducted at the National Institute for Biological Sciences and Safety (Sagamihara City, Kanagawa Prefecture).The experimental protocol was approved by the Institute for Biological Sciences and the Animal Experiment Committee of Azabu University (No. 160926-1, No. 161102-1) was obtained.Forty-two 68-week-old laying hens (Julia Light: Kanagawa Chuo Poultry Farming Cooperative, Sagamihara City, Kanagawa Prefecture) with no abnormalities in general condition were used for the experiment. We tested 11 interconnected wire mesh cages for laying hens (depth x width x height: 40 x 24 x 45 cm) in four locations in a closed chicken house, and each cage housed one chicken. The lights were kept on for 15 hours from 4:00 to 19:00.The feed was fed ad libitum with a compound feed for raising adult chickens, ``Egg Partner 17'' (JA Kumiai Feed Co., Ltd.) using a gutter-type feeder. ,Feeders were installed for each test group.

2. Animal testing

The egg-laying rate of the 42 test chickens was measured during 13 days of acclimatization, and 30 chickens with good egg-laying rates were used in this test, and the rest were not used in the test.70 weeks after the end of acclimatization. The above 30 birds were divided into three groups of 10 birds at each age to ensure uniform spawning status.A commercially available silicon agent (umo®, APA Corporation, silicon concentration = 8 mg/mL) was used. , diluted with tap water to a final concentration of 1% (v/v) and 5% (v/v), and the test group was divided into a control group (tap water without additives) and a low-dose group (1%), respectively. and a high-dose group (5%).These silicone agents were given to the test chickens ad libitum using a reservoir drinking device.

3. General observations

During the 70-day administration period (10 weeks), water consumption and silicate (Na2SiO3) dosage, general condition (activity level, appetite, feather condition, and fecal condition), body weight, weight gain, feed intake, spawning condition, Individual egg weight was observed or measured.

4. Egg quality test

All eggs laid 5 and 10 weeks after the start of administration were observed or measured for eggshell quality, eggshell strength, presence of foreign matter in the egg, egg yolk, Haugh unit value (HU), and eggshell thickness. Collected eggs The eggs were immediately stored in the refrigerator, and the egg quality was tested in the morning of the next day.The eggshell strength was measured using an eggshell strength meter (Fujihei Kogyo Co., Ltd.), and the egg yolk was measured using a Roche York Color Fan (DSM Nutrition Japan Co., Ltd.). Co., Ltd.), HU was measured using an Egg multi-tester (EMT-5200, JA Zen-Noh Tamago Co., Ltd.), and eggshell thickness was measured using an eggshell thickness meter (FN595, Fujihei Kogyo Co., Ltd.). Ta.

5. Free amino acid analysis in eggs

Among the eggs laid at 5 and 10 weeks after the start of administration, the yolk and albumen of each individual were separated and collected.The yolk was left untreated, and the egg white was separated into watery albumen with a blade after the chalaza was removed. and thick egg whites were mixed in a slicing motion to make them homogeneous, then each was placed in an airtight polyethylene bag, the air removed and sealed, and stored frozen at -70°C or below. After half-thawing the egg yolks and egg whites, they were mixed with 3% sulfosalicylic acid. After concentrating to dryness using a rotary evaporator, the sample solution was diluted to 5 mL with distilled water. Various free amino acids and amino acid-related compounds were extracted using an ODS column (InertSustain Swift C18 4.6 mm x 150 mm) after NBD derivatization. Quantitative analysis was performed by HPLC using GL Sciences). Acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid solution were used as the mobile phase, and analysis was performed using the gradient method. Flow rate 1.0 mL/min, injection volume 20 μL, oven temperature The temperature was 40°C, and detection was performed using fluorescence detection (excitation wavelength: 470 nm, fluorescence wavelength: 540 nm).

6. Mechanical strength analysis of descending aorta

Ten weeks after the start of administration, the descending aortas were cut out and collected from the control, low-dose, and high-dose groups in the range of 20 mm to 30 mm. The stress-strain characteristics were recorded at a tensile speed of 30 (mm/min) until rupture.The tester was connected to a load cell with an upper limit of 50N.The stress was determined by the size of the aorta. The maximum stress at rupture was defined as the mechanical strength.

7. Statistical analysis method

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error. For data that required statistical analysis, one-way analysis of variance was performed, and for those that showed differences between groups, Tukey's multiple comparison test was performed. ρ value Differences were considered statistically significant if <0.05.

Experimental result

1. General observations

There were no differences in water drinking, silicate dosage, feed intake, or egg weight between any of the groups.In addition, no significant differences were found in egg production rate, body weight, or weight gain (Table 1). During the administration period, no abnormalities were observed in the general condition or fecal appearance of any of the animals except for one bird. In one bird in the low-dose group, an abnormality was observed 22 days after the start of silicon administration. A decrease in vitality and appetite was confirmed, and the animal died on the 32nd day after the start. An autopsy determined that the cause of death was peritonitis due to egg drop syndrome. Since no abnormalities were observed, the test was continued.The dose ratio of silicon in this test was low dose group: high dose group = 1:4.909.

Table 1 General observation data during the administration period

Data are shown as mean ± standard error. n=9~10

Table 2 Egg quality test 10 weeks after starting treatment

Data are shown as mean ± standard error. n = 9~10

2.Egg quality test

No significant differences were observed in eggshell strength, egg yolk, HU, and eggshell thickness at any time point (5 weeks or 10 weeks after the start of administration) or between groups (Table 2).

3. Free amino acid analysis in eggs

There were no significant differences in free amino acids in egg whites at 5 and 10 weeks after the start of administration, and in egg yolks at 5 weeks.Changes were observed in the amount of free amino acids in egg yolks at 10 weeks, including aspartic acid (Asp) and alanine. Significant increases in (Ala) and threonine (Thr) were observed in the high-dose group compared to the low-dose group (Table 3).

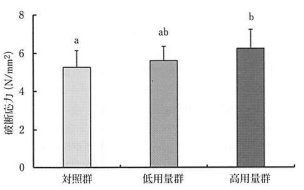

4. Mechanical strength analysis of the descending aorta

In the descending aorta sampled 10 weeks after the start of administration, the mechanical strength of the blood vessel increased in a concentration-dependent manner due to silicon administration, and a significant increase was observed in the high-supplement group compared to the control group (Figure 1). .

Consideration

In this study, a commercially available silicon agent (umo®: APA Corporation, silicon concentration = 8 mg/mL) was administered at 1% (v/v; low dose) or 5% (v/v: The test substance was added to the final concentration (high dose) and administered continuously for 10 weeks. From the calculated dose ratio (low dose group: high dose group = 1: 4.909), the appropriate amount of test substance was administered to the test group. It can be said that the drug was successfully applied.No changes were observed in the general condition, weight gain, egg production rate, etc. of each individual, and almost no abnormalities in egg shell quality were observed in the eggs.From these results, long-term administration to laying hens was not recommended. It is assumed that silicon is not toxic in the concentration range set in this study. Also, no significant differences were observed in eggshell strength, egg yolk, Howe unit value, and eggshell thickness between the groups. According to McCormick, administration of sodium aluminosilicate to laying hens increases eggshell strength, but this phenomenon is different in summer and winter, and they report that eggshell strength does not change in winter when the outside temperature is low9). Since the rearing period in this study was 10 weeks from October to December, it is possible that eggshell strength did not change due to the influence of outside temperature.

Regarding free amino acid analysis in eggs, Asp.

Asp is a free amino acid that exhibits umami, Ala is an amino acid that exhibits strong sweetness and weak umami, and Thr is an amino acid that exhibits sweetness.10) High doses of silicon intake increase the umami and sweetness of egg yolks. As there are few reports on the effects of silicon on free amino acids in tissues, there are many unknowns regarding the mechanism of action of these quantitative changes. 11) It has been reported that silicon deficiency reduces the activity of ornithine transaminase, which is involved in amino acid metabolism in the liver.12) Furthermore, in our previous study using broiler chickens, we found that Similar to this study, increases in Asp, Thr, and Ala have been confirmed in meat and breast meat8).Based on these, silicon intake is involved in amino acid metabolism in the body, and in chickens, especially Asp and Thr. In addition, although the low-dose group at 10 weeks apparently showed lower levels than the control group, there was no statistically significant difference from the control group. In addition, no changes were observed in any of the amino acids in the 5-week egg yolks of the high-dose group.These results indicate that Asp, Thr, and Ala in the yolks It was surmised that the fluctuation of silicon may require long-term administration or administration of more than a certain amount of silicon.

The mechanical strength of blood vessels was significantly increased in the high-dose group compared to the control group.Silicon is known to be an important element in connective tissue1), and silicon has been shown to maintain cardiovascular function. It has been reported in humans and human tissues that silicic acid is important for collagen synthesis in osteoblasts and that silicic acid promotes collagen synthesis in osteoblasts13)14).In addition, studies using chicken chicks have shown that silicon

It has been reported that silicon is a necessary nutrient for connective tissue formation15), and in a study using chondrocytes derived from chicken embryos, it has been reported that silicon promotes collagen synthesis16). It was inferred that silicon intake increases the mechanical strength of blood vessels in laying hens by promoting collagen synthesis in the blood vessels.

The above results suggest that silicon may contribute to improving the taste and sweetness of egg yolks as well as increasing the mechanical strength of blood vessels in laying hens. Although this indicates that it may be useful, further investigation is required to evaluate its effectiveness, including estimation of the appropriate concentration range.

Table 3 Free amino acid content in egg yolk 10 weeks after the start of administration

N.D.; Not detected.

Data are shown as mean ± standard error. There is a significant difference between different signs (ρ<0.05).

n=9~10

Breaking Stress

Symmetric group Low dose group High dose group

Figure 1: Breaking stress in the descending aorta 10 weeks after the start of administration

Data are shown as mean ± standard error. A significant difference between different symbols.

Yes (ρ<0.05). n=9~10

Summary

In this study, we investigated the effects of administering a commercially available silicon agent to laying hens on the amount of free amino acids in egg yolk and on blood vessel strength. When silicon agents were administered to laying hens in their drinking water for 10 weeks, the amount of free amino acids in egg yolk decreased. Significant increases in aspartic acid, threonine, and alanine were observed in the high-dose (5%) group compared to the low-dose (1%) group. In addition, the vascular strength of the descending aorta was increased compared to the control group. A significant increase was observed in the dose group. The results of this study suggest that ingesting silicon from laying hens may be effective in improving the taste quality of egg yolk and the strength of blood vessels.

References

1) Jugdaohsingh, R. (2007). Silicon and bone health. ). Nutr.Health Aging, 11,99-110.

2) Jugdaohsingh, R.. Tucker, L.K., Qiao, N. Cupples, A.L., Kiel,P.D., and Powell, J. J. (2004). Dietary silicon intake is positively associated with bone mineral density in men and premenopausal women of the framingham offspring cohort.J. Bone Miner. Res., 19, 297-307.

3) Carlisle, E.M. (1972). Silicon: an essential element for the chick. Science, 178, 619-621.

4) Elliot, M.A. and Edwards, H.M. (1991). Effect of dietary ( 29 ) Yamamoto et al.: Effect of silicon intake on spawning period 29 silicon on growth and skeletal development in chickens. J.Nutr., 121, 201-207.

5) Sgavioli, S., de Faria Domingues, C.H., Castiblanco, D.M., Praes, M.F. Andrade-Garcia, G.M., Santos, E.T., Baraldi-Artoni, S.M., Garcia, R.G., and Junqueira, O.M. (2016). Silicon in broiler drinking water promotes bone development in broiler chickens. Br. Poult. Sci., 57, 693-698.

6) Carlisle.E.M. (1976). In vivo requirement for silicon in Articular cartilage and connective tissue formation in the chick. J. Nutr., 106, 478-484.

7) Kawamura, Y., Yokota, Y., Nogata, F., Terasawa, M., Kamijo, T., and Okada, K. (2014). Analysis of stress-strain of rat’s bone and blood vessel with dietary silicon intake. IEICE technical report. ME and biocybernetics, 114, 31-36. (Kawamura, Y., Yokota, Y., Nogata, F., Terasawa, M., Kamijo, N., Okada, N.) Analysis of stress-strain of rat’s bone and blood vessel with dietary silicon intake. IEICE technical report. ME and biocybernetics, 114, 31-36.(Kawamura, Y., Yokota, Y., Nogata, F., Terasawa, M., Kamijo, N., Okada, N.) Analysis of stress-strain of rat’s bone and blood vessel with silicon intake. Technical report of the Institute of Electronics, Information and Communication Engineers (ME and biocybernetics).

8) Yamamoto, J., Sugita. K., Mekaru, A., Kobayashi, H., Yoshinaga, Y., Takagi, Y., Shirai, M., and Asai, F. (2017). Benefical effect of water-soluble silicon on the meat quality and fecal odor of broiler chickens. Journal of Veterinary Medicine, 70, 279-282. (Yamamoto, Junpei, Sugita, Kazutoshi, Mekaru, Ai, Kobayashi, Hisato, Yoshinaga, Yuko, Takagi, Takahiko, Shirai, Akishi, Asai, Fumitoshi. Improvement of meat quality and reduction of fecal odor by administration of water-soluble silicon to broilers, Veterinary Livestock News).

9) Keshavarz, K. and McCormick, C.C. (1991). Effect of sodium aluminosilicate, oyster shell, and their combinations on acid-base balance and eggshell quality. Poult. Sci., 70, 313-25.

10) Ajinomoto Co., Inc. (2003). "Amino Acid Handbook," Industrial Research Institute, Tokyo.

11) Carlisle, E.M. and Alpenfels, W.F. (1984). The role of silicon in proline synthesis. Fed. Proc., 43, 680.

12) Seaborn, C.D. and Nielsen, F.H. (2002). Silicon deprivation decreases collagen formation in wounds and bone, and ornithine transaminase enzyme activity in liver. Biol. Trace Elem. Res., 89, 251-261.

13) Schwarz, K. (1979). Silicon, fiber, and atherosclerosis. Lancet, 309, 454-457.

14) Dong, M., Jiao, G., Liu, H., Wu, W., Li, S., Wang. Q. Xu, D., Li, X., Liu, H., and Chen. Y. (2016). Biological silicon stimulates collagen type 1 and osteocalcin synthesis in human osteoblast-like cells through the BMP-2/Smad/RUNX2 Signaling pathway. Biol. Trace Elem. Res., 173, 306-315.

15) Carlisle. E. M. (1976). In vivo requirement for silicon in articular cartilage and connective tissue formation in the chick. J. Nutr. 106, 478-484.

16) Carlisle, E.M. and Garvey, D.L. (1982). The effect of silicon on formation of extracellular matrix components by chon-drocytes in culture. Fed. Proc, 41, 461. (Received June 7, 2017, accepted August 14, 2017)

Note: This paper is translated from the following URL. The content is provided for reference on the scientific research of the raw material only. Whether APA raw materials are used or not, we hope this research will help increase understanding and awareness of body minerals.

Comments